By Julie Stricker ( jstricker@newsminer.com) Jun 10, 2015

FAIRBANKS — Back in Alaska’s territorial days, it wasn’t uncommon for a gold miner to go berserk in a lonely, remote cabin. A woman on an isolated homestead might fall into severe, debilitating depression, becoming catatonic. The territory also had its share of violent, sometimes mentally ill residents. At the time, mental illness was considered a crime.

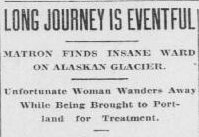

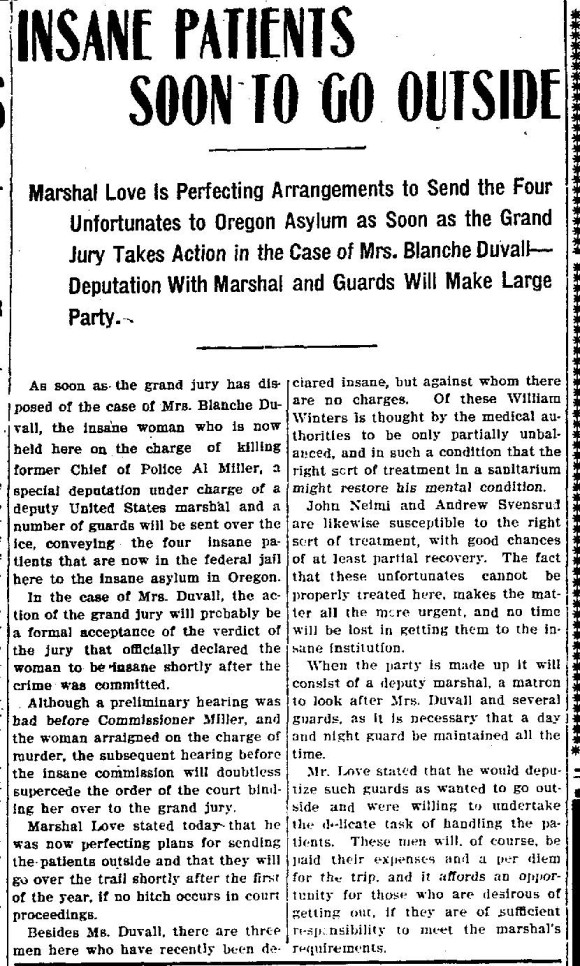

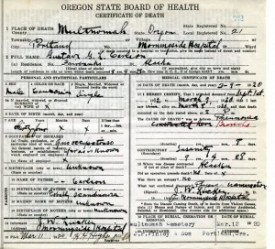

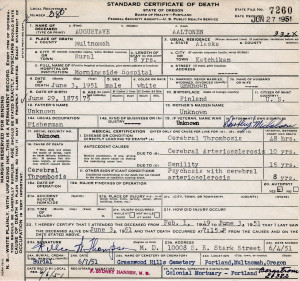

Alaska lacked mental health facilities, so people who were mentally ill or incapacitated were shuttled into the justice system. If deemed insane by a jury, they were sent on a 2,000-mile journey by dog sled, horse-drawn sleigh, barge or boat to Morningside Hospital in Portland, Oregon. Few returned.

“People just disappeared,” said retired Alaska Superior Court Judge Niesje Steinkruger. “And many families had no idea what happened.”

Steinkruger and a group of researchers have been searching through territorial court records to find out the stories behind those sent to Morningside. She calls them the “Lost Alaskans” and will talk about her hunt through Alaska’s territorial court records for their stories in a University of Alaska Fairbanks Discover Alaska lecture on June 17.

Steinkruger is uncertain how many people were sent to Morningside during territorial days. The term “insane” covered a broad range of conditions, including mental illness, birth defects, drug abuse and alcoholism.

Families were torn apart.

“The youngest person we found was 6 weeks old, and the oldest was 96,” she said. The youngest were most likely severely developmentally handicapped. Many had Down syndrome or birth defects.

“It was a family trying to cope with a child that had special needs, and you knew that the only way families could care for a child with severe special needs was this horrible option,” she said.

Sometimes people, such as chronic inebriates, were sent to Morningside as a way to keep them from freezing to death on the streets.

“You have to consider the times. This was before psychiatry,” she said. “There were people there (at Morningside) with epilepsy and substance abuse and everything, including mental illness. Most of the treatment was about safety and a place to live. It was before pharmacological treatment.”

Steinkruger said her goal has been to gather a list of names of those sent to Morningside, many of whom never left Oregon and are buried in the Portland area. The hospital closed in the 1960s and all the records were lost. The lists may be able to help families looking for lost relatives find more information on what happened to them.

As she reads through the territorial records, Steinkruger said she’s struck by parallels to today’s criminal justice system.

“There’s just this huge cross-section of exactly the same problems we’re struggling with today,” said Steinkruger, who served as a judge for 19 years and also worked with the district attorney and public defenders offices. “The thing that really gets me is to look at how little has changed. We are still grappling with exactly the same role between safety, care, treatment and protection.”